Back in the 1990's, John Woodward (the proprietor of JW Engineering) was given a complete set of castings from an original Victorian, John Holman, Cornish Range. Being an engineer, he decided to find out how it worked and the history behind, what he found to be, a really efficient cooking and heating appliance. Several years later, as a hobby, John set about making a new Cornish Range for himself and the result is shown pictured above. Consequently, we now own approximately 200 related drawings for the 30" wide Cornish Range from which we are able to supply replacement parts and castings. If you own a Cornish Range which is tired and in need of a face lift, we also offer a refurbishment service.

This video was created by one of our customers and gives an insight as to what can be achieved when we refurbish a Cornish Range.

The photographs depict the original condition of the Cornish Range before and during the restoration of ironwork and rebuild, whereas the video at the end shows the refurbished Cornish Range in all its glory being used as a fully functioning cooking and heating appliance.

The castings were carefully dismantled and taken away to be shot blast. When they arrived back to our workshop we applied a special high temperature paint. We made a new metal canopy and restored or replaced several parts before rebuilding the Cornish Range in the traditional manner and giving it another coat of paint.

Our thanks go to Greg Cording for giving us permission to use his video on our website.

CORNISH RANGE DESIGNS

HISTORY OF THE CORNISH RANGE

The Cornish Range was known locally as a ‘Slab’ (this being another name for a hotplate). It was the most efficient and decorative of the Victorian kitchen ranges.

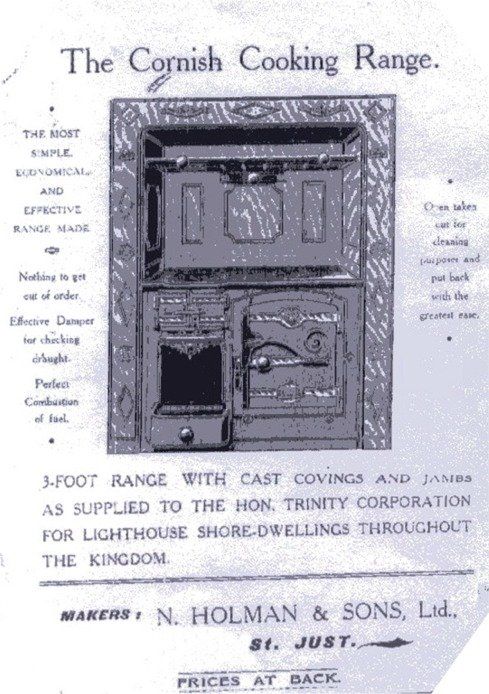

What little research has been done indicates that the general arrangement arrived around the 1830’s in Redruth. They remained in production until just before the Second World War, the last being made by St. Just Foundry in Penwith.

During the mid to late Victorian age, just about every Cornish house would have had a Cornish Range, from the most common 30 inch wide hotplate in the working class cottage to the huge Manor House ranges with slabs up to 6 feet in length.

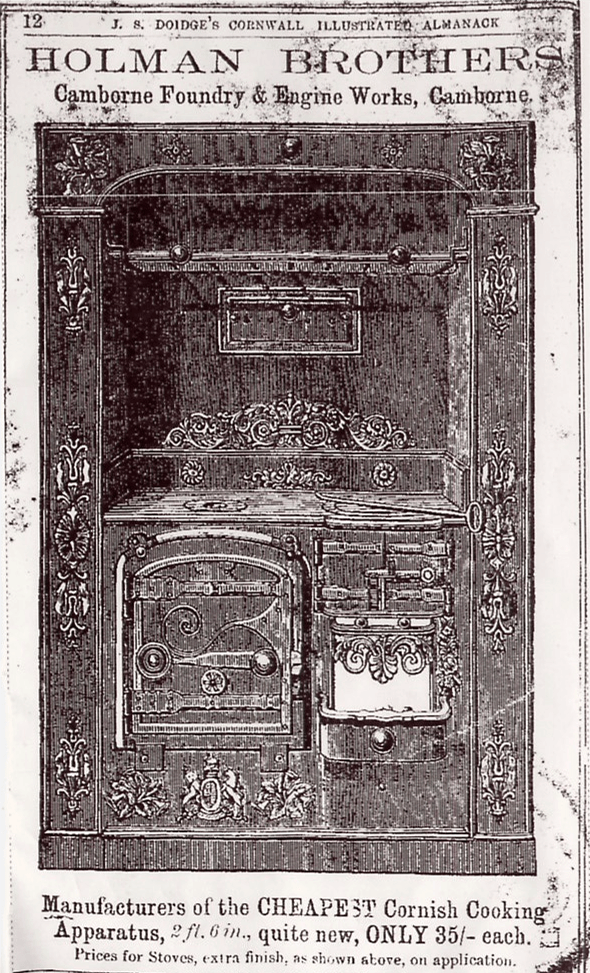

During this period, apart from the big foundries like Harvey's, Copperhouse, Holman's and Piran, most Cornish towns had one or more small foundries, especially if they were situated in one of the mining districts. All of these foundries, apart from selling complete ranges themselves, would also sell castings to the towns and village blacksmiths to complete in their own style and sell under their own name.

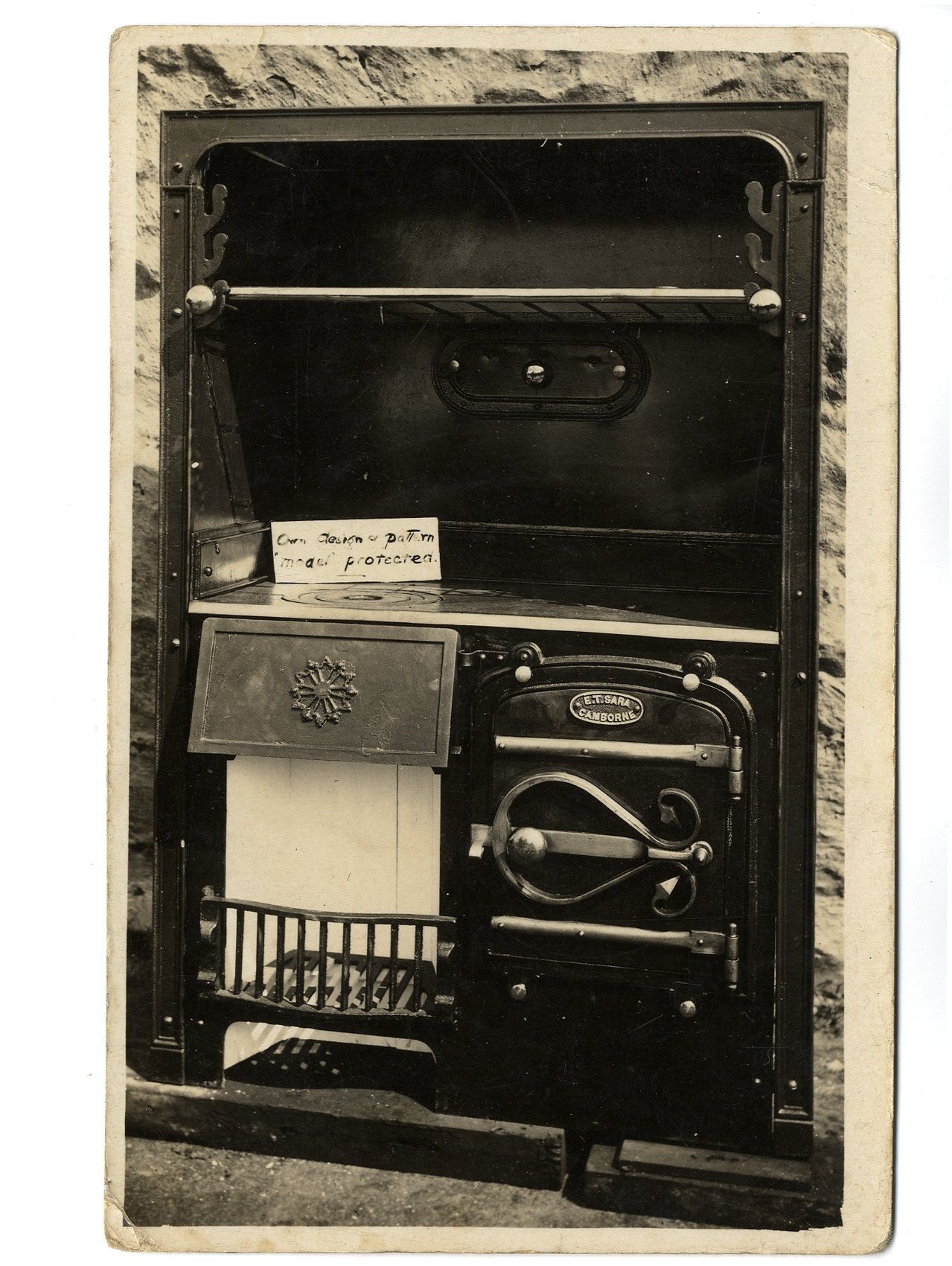

Using Camborne as an example, there was the huge foundry and engineering works of John Holman, situated in the north-east of the town, the smaller foundry of E T Sara at the foot of Trevu Hill and somewhere in the town a blacksmith by the name of W Jenkin. All making and selling ranges under their own name.

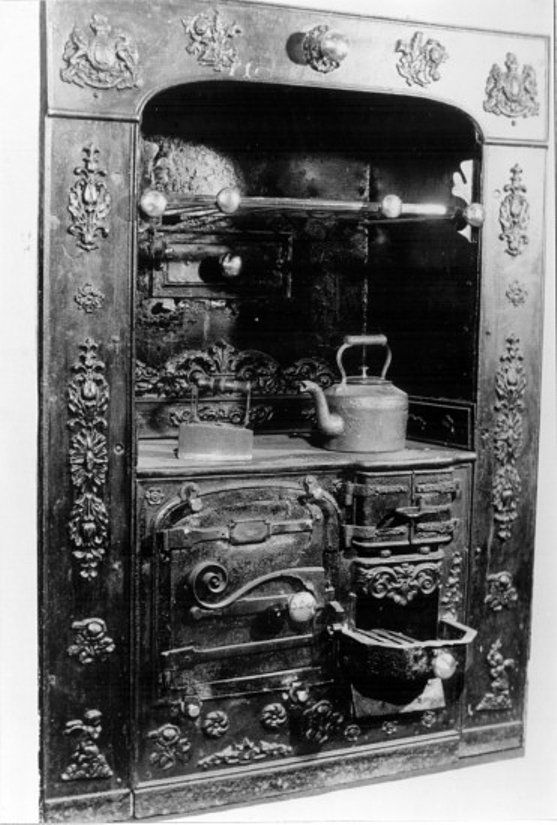

One decorative relief common to most ranges is the Royal Coat of Arms, which is normally featured once, if not twice. Whereas the majority of the decorative designs are flowers, fruit and neo-classical scrolls etc. One unusual feature, which occurs quite often but as yet to be explained, is a bird with an eagles beak and a crest on its head.

The foundries have certain key designs which are generally incorporated and these can be used to identify the castings, for example, Holman's of Camborne normally have a large rose, thistle and shamrock in a cluster below both lower corners of the oven.

As originally designed, the range has a body built from Common London Brick, approximately 160 in a 30” slab, all held together with lime mortar plus a small number of fire bricks for the fire box.

There were several methods of operation, the most common being the hot smoke passed over the top of the oven, down the far side, then underneath. From there it would travel into a central brick flue which ran from the foot to the top of the range. Two thirds of the way up the flue was the damper to control the draught. This was pulled out to open and was the main way of controlling the fire, albeit not very efficiently, hence the section of verse in a well-known Cornish folk song ‘you push the damper in and you pull the damper out and the smoke went up the chimney just the same’.

Some were designed with ovens on the left-hand side and others on the right-hand side to suit the chimney in the house. Later ones were fitted with back boilers.

This demise was brought about by several things, ie. The disappearance of the numerous towns and village foundries which had relied so heavily on the 19th century mines coupled with the arrival of modern ranges like Aga and Raburn etc.